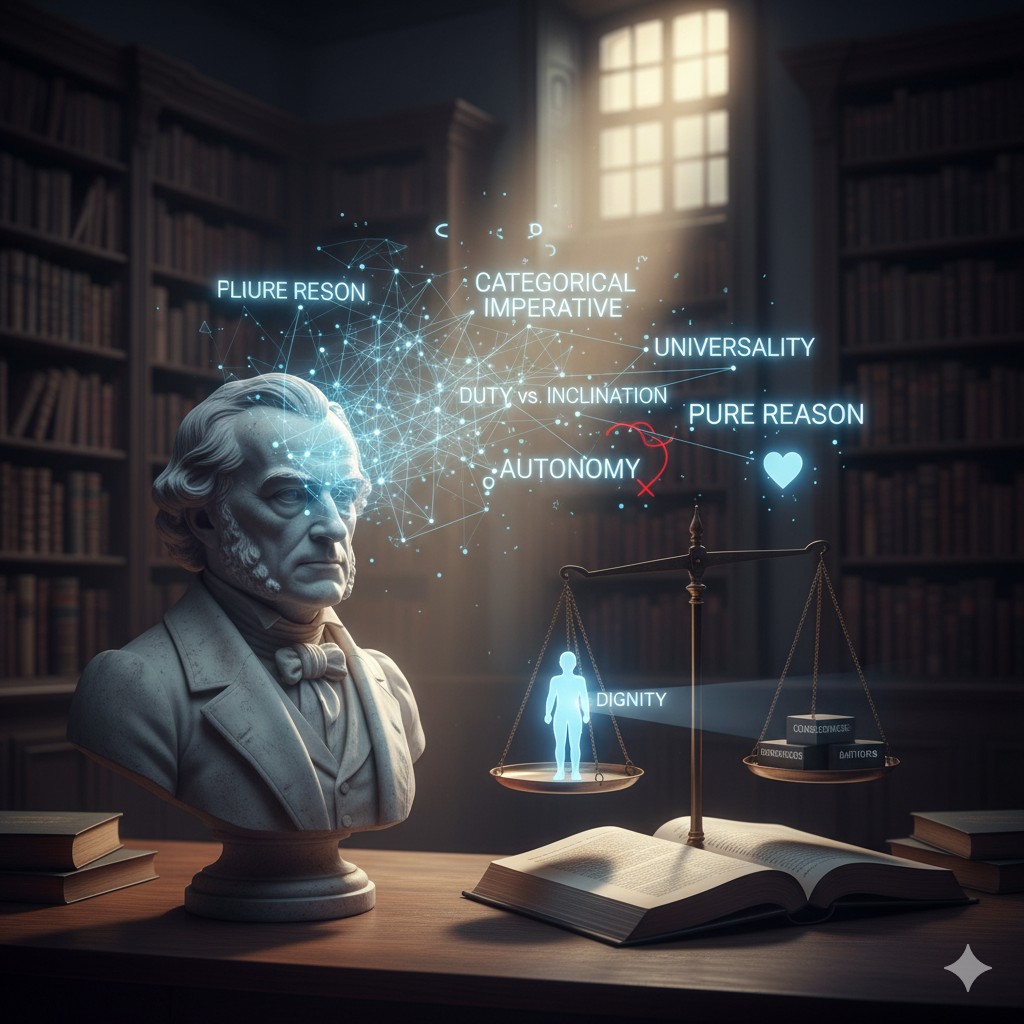

What did Immanuel Kant base his ethics on?

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) stands as one of the most towering and influential figures in the history of Western moral philosophy. His ethical theory, known as Kantian ethics or deontology (from the Greek word deon, meaning duty), fundamentally changed how philosophers and thinkers approach morality.

Kant's theory is a radical departure from ethical systems that ground moral worth in consequences, such as utilitarianism, or in emotions like sympathy or compassion. Instead, Kant’s ethical universe is built on the unshakeable foundation of reason, duty, and a universal moral law. For Kant, an action isn't moral because of what it achieves, but because of the good will—the pure motivation—behind it. We will clearly explain the bedrock foundations of Kantian ethics, focusing on its core concepts: the categorical imperative, the critical distinction between duty and inclination, the centrality of autonomy, and the role of universal moral law.

What Is the Categorical Imperative in Kant's Ethics?

The categorical imperative is the single, central moral principle of Kant’s ethical system. In essence, it is the ultimate command of reason, an unconditional moral obligation that is binding on all rational beings, regardless of their personal desires or the potential consequences of their actions.

To understand it, Kant first distinguished it from a hypothetical imperative, which is a conditional command: "If you want X, then you must do Y" (e.g., "If you want to pass the exam, you must study"). The hypothetical imperative is goal-oriented; its necessity depends on a preceding desire.

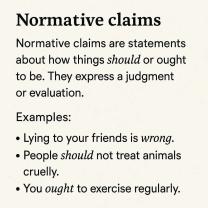

The categorical imperative, by contrast, is an unconditional "ought." It dictates action simply because the action is morally right, not because it leads to a desirable outcome. It is a universal law that applies absolutely. Kant presented the categorical imperative in several equivalent formulations, but the two most famous are:

The Formula of Universal Law: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

In practice: Before acting, you must consider the underlying maxim (the rule or principle behind your action) and ask if you could rationally will that everyone adopt this maxim as a universal, binding law. For instance, if your maxim is "I will make a false promise when it benefits me," you must universalize it. If everyone made false promises, the very concept of a promise would lose all meaning, creating a logical contradiction in conception. Since this universalization is rationally impossible, the original action (making a false promise) is morally forbidden.

The Formula of Humanity as an End in Itself: "Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end."

In practice: This formulation highlights the intrinsic value of rational beings. It is wrong to use people as mere tools or objects to achieve your goals without respect for their own rational will and goals. Treating a cashier with basic courtesy is treating them as an end (a person with dignity) as well as a means (a way to complete a transaction); coercing or manipulating someone, however, is treating them merely as a means.

How Does Kant Differentiate Between Duty and Inclination?

A cornerstone of Kantian ethics is the distinction between duty and inclination, which determines an action's moral worth.

Inclination refers to actions motivated by personal desires, feelings, emotions, or anticipated outcomes, such as self-interest, compassion, or a search for happiness.

Duty is the necessity of acting out of respect for the moral law—the categorical imperative—simply because it is the right thing to do.

For Kant, only actions performed from duty have genuine moral worth.

The Moral Weight of Motivation

An action may be in conformity with duty (i.e., it aligns with what duty requires), but if it is motivated by inclination, it lacks true moral value.

Scenario Example:

Shopkeeper A gives honest change to a customer because he is an honest person who genuinely enjoys being fair. (Act is in accordance with duty, motivated by inclination/honesty.)

Shopkeeper B gives honest change to a customer because he knows that if he's caught cheating, he'll lose his business, which would hurt his bottom line. (Act is in accordance with duty, motivated by self-interest/inclination.)

Shopkeeper C gives honest change to a customer solely because he recognizes it is his moral duty to not deceive others, even if he secretly wanted to cheat them and believed he could get away with it. (Act is from duty, motivated by respect for the moral law.)

Kant argues that only the action of Shopkeeper C has moral worth. A and B's actions are commendable and right, but their motivation is contingent on personal feeling or self-interest. Only C acts from the pure recognition of moral obligation, which, for Kant, is the only unshakable foundation for morality.

Why Is Autonomy Central to Kant's Moral Philosophy?

The concept of autonomy (Greek for "self-governance") is absolutely central because it is what gives the moral law its binding force and gives humans their unique dignity.

Kant argued that moral freedom—the ability to be a moral agent—comes from autonomy of the will. It is the ability of a rational being to be a law unto itself by recognizing and freely choosing to obey the rational moral law (the categorical imperative) that is inherent in its own reason.

Kant contrasts this with heteronomy (governance by something else). A will that is governed by external forces, such as the command of a ruler, a religious text, or even internal forces like desires, inclinations, or the pursuit of happiness, is heteronomous. In such cases, the agent is simply a tool for an end determined elsewhere; they are not truly free in the moral sense.

For Kant, our actions are genuinely moral only when they spring from a will that is autonomous—one that legislates the moral law for itself through reason and then acts from duty to obey that self-legislated law. This capacity for rational autonomy is what gives every human being their unique dignity and why we must never be treated merely as a means to an end.

How Does Reason Shape Kant's Ethical Principles?

Reason is the ultimate foundation of Kant’s morality. Kant believed that moral principles are not derived from empirical observation of the world, emotional sentiment, or consequences, but are purely a priori (known independently of experience).

Morality as Rational Law: Since morality must be universally binding and absolutely necessary, it cannot be based on subjective feelings, which vary from person to person. It must be based on pure practical reason, a faculty shared by all rational beings.

Recognizing Universal Laws: Kant argued that any rational being, by merely reflecting on the concept of action and law, is compelled to recognize the categorical imperative. Reason is the tool that allows us to test our maxims for universality and consistency.

Rising Above Impulse: Reason is what liberates humans from being slaves to their impulses and inclinations. It provides a higher motivation—the respect for the moral law—which allows us to choose to act ethically even when it conflicts with our self-interest or desires. In this way, the ethical life is the truly rational life.

What Role Does Universality Play in Kant’s Moral Framework?

Universality is not just a feature of Kant's ethics; it is the test for moral permissibility, as captured in the first formulation of the categorical imperative.

The idea of universality means that a moral action is one that is valid for all rational beings, in all times, and in all relevant circumstances.

When you formulate a maxim for your action, the test of universality asks: "Could I rationally will that everyone act on this principle?"

Example: The Lie: Imagine your maxim is "I will lie to get out of trouble."

If you universalize this maxim, you are willing a world where everyone lies when it suits them.

But in a world where everyone lies, the institution of communication and truth-telling collapses; no one would believe a statement of intent, and therefore, the very act of lying to achieve a goal becomes self-defeating and rationally impossible. This "contradiction in conception" proves that the original action (lying) is morally wrong and cannot be universalized.

The universality principle ensures fairness and consistency. By requiring that moral laws be applicable to everyone, including ourselves, it prevents us from making self-serving exceptions and treats all rational agents as equal subjects of the moral law.

Comparison: Kantian Deontology vs. Consequentialism

Kantian ethics belongs to the family of deontological theories, which judge actions based on adherence to rules or duties, irrespective of outcomes. This stands in stark contrast to consequentialist theories, such as utilitarianism (championed by philosophers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill).

| Feature | Kantian Deontology | Consequentialism (Utilitarianism) |

| Foundation of Morality | Duty and rational moral law (Categorical Imperative). | Consequences (achieving the greatest good/happiness for the greatest number). |

| Moral Action | An action is right if it is done from duty, regardless of the outcome. | An action is right if it produces the best overall result/utility, regardless of the intent. |

| Intrinsic Value | Humans have intrinsic value (dignity) and are ends in themselves. | Value is determined by contribution to overall utility; no individual right is absolute. |

Where a utilitarian might justify sacrificing one innocent person if it leads to the happiness of millions, a Kantian would strictly forbid it, as it violates the perfect duty to treat that person as an end in themself and not merely a means.

FAQ Section

What is the categorical imperative in simple terms?

In its simplest form, the categorical imperative is an unconditional moral rule that reason dictates you must follow. It commands you to act only on principles that you could rationally will every other person to act upon, and always to treat people—including yourself—with respect as valuable ends in themselves, never just as tools.

Why does Kant say acting from duty has more moral value than acting from kindness?

Kant argues that moral value must be unconditional and universal. Kindness, compassion, or sympathy are commendable, but they are inclinations—feelings that are subjective, unreliable, and contingent (you might feel kind one day but not the next). An action done from duty, however, is motivated by a pure, rational recognition of the moral law, which is a steadfast and universal principle. Therefore, only the action from duty provides the necessary, unwavering foundation for true moral worth.

How does Kantian ethics apply to modern ethical issues?

Kantian ethics provides a powerful framework for debates in areas like human rights and justice. The Formula of Humanity (treating people as ends, not means) is the direct philosophical grounding for the idea that human rights are absolute and cannot be violated, even for the sake of the greater good. In modern dilemmas, it requires us to consider whether our actions respect the rational autonomy and dignity of all involved.

Conclusion

Immanuel Kant based his ethical system on the unshakeable pillars of reason, duty, autonomy, and universality. He posited that genuine moral worth comes from a good will—the decision to act from duty out of respect for the moral law. This law is encapsulated in the categorical imperative, an unconditional command that binds all rational beings.

By emphasizing the rational self-governance (autonomy) of the moral agent and demanding that moral rules be capable of universalization, Kant established a deontological framework where moral law is an expression of pure practical reason. His moral philosophy continues to shape modern ethical debates, serving as a powerful and enduring reminder that true morality rests on principles of fairness, consistency, and the absolute dignity of every human being.

Ethics_Compared

on October 03, 2025The final comparison to consequentialism was highly useful. It starkly illustrates the difference: consequences don't matter to Kant; the only thing that matters is the purity of the motive derived from **duty** and the Categorical Imperative.

End_in_Itself_User

on October 03, 2025The 'humanity as an end in itself' formulation is the most impactful to me. It's the philosophical bedrock for modern human rights—the absolute rule that we can never use another person merely as a means to our own gain. It’s a timeless ethical principle.