Was Immanuel Kant a theist or atheist?

1. Introduction: Navigating Kant's Complex Stance on God

Immanuel Kant stands as a towering figure in the history of philosophy, whose "critical philosophy" profoundly reshaped metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics. His work, particularly the three Critiques, aimed to reconcile the seemingly disparate doctrines of rationalism and empiricism, ultimately establishing the inherent limits of human reason while simultaneously affirming its profound power in shaping moral life. He is credited with eradicating the last vestiges of the medieval worldview from modern philosophy, forging a powerful model wherein the fundamental principles of both science and morality originate from human subjectivity.

Central to understanding Kant's comprehensive philosophical system is his intricate and often misunderstood stance on the existence of God. The question "Was Kant a theist or atheist?" demands more than a simple binary answer; it necessitates a deep dive into the nuanced interplay between his theoretical philosophy (what can be known) and his practical philosophy (how one ought to act). Kant's position is complex and has been, and continues to be, a subject of extensive scholarly debate. He cannot be neatly categorized as either a traditional dogmatic theist or an outright atheist.

The complexity of Kant's position is perhaps best encapsulated by his famous dictum: "I have therefore found it necessary to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith". This statement is not a casual remark but a foundational principle of his critical project concerning religion. It signals a deliberate philosophical strategy to delineate the boundaries of theoretical reason, thereby creating a legitimate space for belief in God, not as an object of empirical or metaphysical knowledge, but as a necessary presupposition for the coherence of moral life. This philosophical maneuver, where knowledge is systematically limited to clear the intellectual ground, ensures that if theoretical reason could definitively prove or disprove God's existence, then faith would either be redundant or impossible. By rigorously demonstrating the inherent boundaries of theoretical reason and its inability to provide knowledge of transcendent objects like God, Kant establishes a distinct, non-empirical, and ultimately more secure basis for belief. This re-orientation of the problem of God's existence from the theoretical to the practical realm ensures that morality, which Kant considered foundational to human reason, could have a rational basis without relying on the shaky ground of speculative metaphysics.

The Enlightenment era, of which Kant was a central figure, was characterized by a profound emphasis on human reason and a critical questioning of traditional religious authority and dogma. Many Enlightenment thinkers, following the trajectory of rational critique, moved towards deism or even outright atheism. Kant, however, while participating in this critique, particularly by dismantling traditional proofs for God's existence, sought to preserve a rational basis for religious belief, albeit in a transformed guise. His concept of "moral faith" represents a sophisticated attempt to reconcile the rigorous demands of Enlightenment rationality, which necessitated the critique of speculative metaphysics, with what he perceived as the inherent human need for moral purpose and the possibility of a "highest good," which he believed required the postulate of God. This suggests a broader implication: Kant's project can be viewed as an ambitious effort to construct a form of religion that is not only compatible with but also grounded in autonomous human reason, rather than relying on external revelation or unprovable metaphysical claims. This represents a profound redefinition of religion for the modern age, shifting its primary locus from speculative theology to practical ethics and individual moral responsibility. This report will meticulously explore this unique "moral faith," dissecting his critiques of traditional proofs, explicating his moral arguments, and examining his mature religious philosophy to provide a comprehensive and nuanced answer to the query.

2. Defining Theism and Atheism in Context

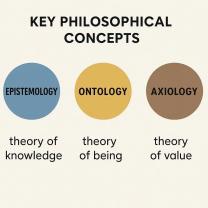

To accurately position Kant's views, it is crucial to establish clear definitions of the terms "theism" and "atheism," as well as related concepts that frequently arise in discussions of his philosophy.

Theism: In its standard usage, theism refers to the belief in the existence of a divine reality. This typically denotes monotheism—the belief in one God—who is often conceived as distinct from Creation (transcendent) and capable of controlling events from outside the human world. Theism often grapples with the dual nature of God as both transcendent (beyond human experience) and potentially immanent (having existence and effect within human consciousness and the material world).

Atheism: Broadly defined, atheism is the absence of belief in the existence of deities. More narrowly, it constitutes a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. It is important to note that atheism is not inherently a belief system or a religion itself, but rather a lack of conviction regarding the assertion that gods exist. It does not necessarily provide answers to questions of creation or evolution, but simply expresses an unconvinced stance on the existence of deities.

Related Concepts:

Deism: While not explicitly defined in the provided material, deism generally refers to the belief in a God who created the universe but does not intervene in its affairs. Kant's emphasis on God as a "regulative" principle for theoretical reason , rather than a direct, intervening causal agent, might lead some interpretations to associate his views with deistic leanings. However, his moral argument for God's necessity in the pursuit of the highest good goes beyond the purely distant creator of classical deism.

Agnosticism: This philosophical position asserts that the existence of God is either unknowable in principle or currently unknown in fact. Kant is frequently described as defending a "principled agnosticism" concerning the

theoretical knowledge of God. Within agnosticism, there are distinctions: "agnostic atheism" combines a lack of belief in deities with the claim that their existence is unknowable, while "agnostic theism" involves a belief in God despite acknowledging that such existence cannot be definitively known. Kant's position aligns more closely with agnostic theism, as he posits the necessity of belief despite the theoretical unknowability of God.

Traditional philosophical and theological discourse often conflates the concepts of "belief" and "knowledge," particularly when discussing the existence of God. Kant, however, introduces a crucial and systematic separation between them. He rigorously asserts that knowledge (or theoretical cognition) of God is fundamentally impossible due to the inherent limitations of human intellect, which is confined to the realm of sensory experience and phenomena. Yet, simultaneously, he argues for the

necessity of belief (faith) in God, not on empirical or metaphysical grounds, but on the distinct basis of practical reason. This is not a mere concession or a weaker form of knowledge, but a distinct epistemic attitude with its own rational justification. This systematic separation reveals that Kant is not simply stating, "we do not know, so we believe anyway," but rather, "we

cannot know God as an object of theoretical cognition, but we must believe in God as a postulate for the sake of making our moral striving coherent and rational." This redefines the very terms of the debate about God's existence, shifting the focus from empirical or metaphysical proof to the realm of moral necessity and the internal demands of practical reason.

3. The Limits of Theoretical Reason: What Cannot Be Known (Critique of Pure Reason)

In his seminal work, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781, 1787), Immanuel Kant embarked on a profound examination of the nature and limits of human understanding. He positioned his philosophy against both the excesses of rationalist metaphysics, which claimed to derive knowledge of God and transcendent realities through pure reason alone, and the limitations of empiricism, which confined knowledge strictly to sensory experience. Kant's primary aim in this critique was to establish the strict boundaries within which human reasoning could legitimately operate, asserting that reason falls into contradiction and confusion when it attempts to transcend these limits.

A cornerstone of the Critique of Pure Reason is Kant's systematic dismantling of the traditional metaphysical arguments for God's existence: the ontological, cosmological, and physico-theological (teleological) proofs. Kant contended that human knowledge is inherently constrained by the limits of pure reason, which requires an empirical component for knowledge. God, as a transcendent being, exists beyond the reach of our sensory experience and thus cannot be an object of theoretical knowledge. He criticized the tendency to anthropomorphize God, attributing human qualities and concepts to a divine entity, arguing that this approach inevitably leads to confusion and contradictions in arguments for God's existence. Regarding the ontological argument, Kant famously argued that "existence is not a predicate". Adding "existence" to the concept of a perfect being does not add to its perfection; it merely states that the concept is instantiated in reality. Therefore, one cannot logically deduce existence from a mere concept. He further demonstrated that the cosmological argument and the teleological argument ultimately rely on the flawed ontological argument or attempt to extend reason beyond its legitimate empirical boundaries. The overarching conclusion of the

Critique of Pure Reason concerning God was that pure theoretical reason must be restrained; it produces confused and contradictory arguments when applied outside its appropriate sphere of possible experience.

Kant's rigorous and systematic critique of the traditional proofs for God's existence is not merely an intellectual exercise in logical deconstruction. It serves a profound strategic purpose within his broader philosophical project. If God's existence could be proven definitively by theoretical reason, then there would be a strong temptation to derive moral laws from divine commands or from the nature of a known divine being. Such a derivation would, however, undermine the foundational principle of human moral autonomy, which Kant considered paramount. By demonstrating that such proofs are beyond the legitimate scope of theoretical reason, Kant effectively ensures that morality

must find its grounding elsewhere—specifically, in pure practical reason itself. This sets the crucial stage for his ethical system, where human beings are understood as self-legislators of the moral law.

While theoretical reason cannot know God, Kant did not dismiss the concept of God entirely from the theoretical realm. Instead, he argued that the idea of God serves a crucial "regulative" function for reason. This means that the concept of God helps reason to organize and systematize human understanding of the world, guiding inquiries and allowing thought

as if everything came from a single, unified, intelligent source. This "as if" thinking is an analogy, a principle that aids in maximizing systematic unity in nature, but it is not an assertion of God's actual existence as an object of theoretical knowledge or empirical cognition. God, in this context, is a limiting principle in causal accounts of the spatio-temporal world, not a supreme constitutive element or fundamental explanatory principle. Prior to Kant, the traditional metaphysical view often posited God as the ultimate constitutive principle, serving as the fundamental explanatory principle and the absolute causal ground of the world. Kant's redefinition of God as a "regulative" principle, rather than a constitutive one, signifies a profound epistemological and philosophical shift. It implies that the order, unity, and systematicity perceived, or strived for, in the world and in moral lives do not necessarily derive from an external, empirically knowable divine being. Instead, these principles arise from the inherent structure and needs of

human reason itself. This has broad implications for the intellectual landscape and the secularization of thought, as it places the locus of order and meaning squarely within human subjectivity and rationality, rather than solely in a transcendent deity. Even the "God-talk" that remains in Kant's philosophy is fundamentally shaped by human cognitive and practical needs, suggesting that understanding of the divine is deeply intertwined with the structure of the human mind.

4. The Imperatives of Practical Reason: What Must Be Believed (Critique of Practical Reason)

Having established the limits of theoretical reason in the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant turned his attention to the realm of morality and the demands of practical reason in his Critique of Practical Reason (1788). It is here that his famous dictum, "I have therefore found it necessary to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith" , finds its full expression. This statement encapsulates the transition from what cannot be known (theoretically) to what must be believed (practically). While God's existence cannot be an object of theoretical knowledge, belief in God becomes a rational necessity for the coherence and pursuit of the moral life.

Kant argued that morality is fundamentally based on the rational will and duty, rather than on inclinations, desires, or the pursuit of happiness. The supreme principle of morality is the Categorical Imperative, which dictates that one should "Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law". Actions are moral only if performed out of duty, for duty's sake, not for personal gain or happiness. However, human beings, as rational and embodied agents, are also naturally inclined to pursue happiness. This leads to the concept of the "Highest Good" (Summum Bonum), which Kant defines as the perfect union of virtue (moral perfection) and happiness proportional to that virtue. This "highest good" is the ultimate aim of moral actions. While individuals are obligated to strive for virtue, happiness is not necessarily commensurate with virtue in this life; often, the virtuous suffer while the wicked prosper. Kant's principle of "ought implies can" suggests that if one is morally obliged to achieve the highest good, then its achievement must be possible. To resolve this "dialectic between ethical conduct and happiness" and to ensure that moral actions are not ultimately futile or irrational, Kant posits that belief in God is a necessary presupposition. God is required as a perfectly just and powerful being who can guarantee that happiness will ultimately be distributed in proportion to virtue, thereby making the highest good achievable.

These three concepts are not objects of theoretical knowledge, meaning their existence cannot be proven or disproven by empirical or metaphysical means. Instead, they are "postulates"—fundamental assumptions or presuppositions—that are "absolutely essential for moral philosophy". They are necessary for rational beings to make sense of and commit to the moral law.

Freedom: The very possibility of moral action, of acting from duty rather than mere inclination, implies that individuals are free. If actions were entirely determined by natural causality, morality would be an illusion. Freedom is revealed by the actuality of practical life and the moral law itself.

Immortality of the Soul: The achievement of complete moral perfection (holiness) is an endless task, not fully attainable in a finite lifetime. Therefore, to rationally pursue this infinite progression towards virtue, the soul must be immortal.

God: As discussed, God is necessary as the guarantor of the highest good, ensuring that happiness will ultimately correspond to virtue. Only a supreme being could establish this necessary connection between morality and happiness.

The highest good is the ultimate, complete object of the moral will, representing a world where perfect virtue is combined with proportionate happiness. For Kant, this ideal is not merely an aspiration but a necessary aim of moral action. However, the realization of this ideal is not within human power alone. Without the postulate of God, the pursuit of the highest good would appear irrational or ultimately hopeless, which could lead to moral discouragement. Therefore, belief in God provides the rational ground for hoping that moral striving is not in vain and that the world is structured in such a way that the highest good is ultimately possible.

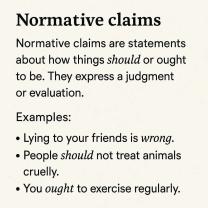

Kant makes a critical distinction: morality, in its motivational force, does not need religion. The moral law, derived from pure practical reason, is sufficient to move a rational agent to act. However, he then asserts that "morality inevitably leads to religion" because the full realization of the moral project – the pursuit of the highest good – requires the postulates of God and immortality. This is a crucial point. God is not the

source of moral obligation or the reason for being moral; rather, God is the condition for the possibility of the ultimate fulfillment of morality and its rational coherence in the world. This indicates that Kant is not making a theological claim about God's existence, but a practical claim about what rational moral agents must presuppose to maintain their commitment to morality without falling into despair or contradiction. It is a pragmatic justification for belief, rooted in the demands of human practical reason, not a metaphysical one.

Traditional arguments for God's existence attempt to prove God's existence from external features of reality: the nature of being, the existence of the universe, or its intricate design. Kant's moral argument, in stark contrast, derives the necessity of belief in God from the

internal nature of human moral experience and the inherent demands of practical reason. This represents a radical anthropocentric turn in theological justification. God's existence is not proven

objectively, as a feature of reality independent of human consciousness, but rather subjectively, as a necessary condition for the coherence and ultimate intelligibility of our moral framework and striving. This implies that the 'God' Kant speaks of is fundamentally tied to human moral striving and the pursuit of the highest good, rather than a detached, abstract entity whose existence is demonstrable apart from human experience. This has profound implications for understanding the nature of religious belief in a post-Enlightenment context, where human experience and reason become the primary lens through which even divine concepts are understood and justified.

5. Religion within the Bounds of Mere Reason: Kant's Mature Religious Philosophy

Kant's engagement with religious thought continued and deepened in his later work, most notably in Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, published in 1793. This work represents an ingenious attempt to address the nature of faith and religious obligation within the framework of his critical philosophy, pushing readers to consider what religious practices are truly necessary for genuine moral conduct.

In this work, Kant provides a precise technical definition of religion: "Religion (subjectively considered) is the recognition of all duties as divine commands". This means that for Kant, a religious person is one who views their moral duties—which are derived from autonomous human reason—as if they were commanded by God. This perspective integrates moral duty with a religious attitude, suggesting that the moral law, though self-legislated, can be revered as if it were a divine imperative. This definition is not a simple return to traditional theological voluntarism, where God's arbitrary will dictates morality. Instead, it represents a profound internalization of the divine command theory. For Kant, the

source of moral commands remains autonomous human reason, but the attitude towards these duties is one of reverence, as if they were divine. This indicates that Kant's project is not to abandon religion in the face of Enlightenment critique, but rather to re-form it. He systematically strips away what he considered external, superstitious, or heteronomous elements, such as ritualistic worship or blind obedience to dogma, and re-centers religion on the moral autonomy and inner disposition of the individual. Religion, for Kant, becomes primarily a matter of inner moral conviction and practical striving, rather than strict adherence to external dogma or ritual. This makes religion robustly rational and universally accessible, independent of specific historical revelations.

Kant drew a sharp distinction between what he called a "religion of pure reason" and "ecclesiastical faith" (Kirchenglaube), which refers to organized, historical religions. He sought to demonstrate that a religion based purely on reason could exist and, furthermore, that it need not conflict with revealed (specifically Christian) religion, but could and should be harmoniously interpreted through the lens of reason. For Kant, there is fundamentally only one true religion, which is rooted in the universal recognition of duties as divine commands, irrespective of specific historical revelations or dogmas.

Kant was a vocal critic of what he perceived as the superficial or superstitious aspects of traditional religious practices. He expressed strong criticisms of external rituals, devotional practices, and hierarchical church structures, viewing them as "counterfeit service to God". He also undertook a rational reinterpretation of core Christian doctrines. For example, he rejected the traditional notion of "vicarious atonement" in favor of an "exemplary" role for Christ, seeing him as a moral ideal. Similarly, his discussions of divine providence, incarnation, miracles, and revelation consistently questioned direct divine intervention within the ordinary causal workings of the natural and human world, aligning with his philosophical distinction between the sensible and the intelligible realms. Despite being raised Pietist (a form of Lutheranism emphasizing personal moral conduct), Kant notably never attended religious services as a professor in Königsberg, a highly unusual practice for his time. Historically, Kant's philosophy is often viewed as contributing significantly to the secularization of modern culture, particularly by discrediting traditional metaphysical arguments for God's existence and replacing God's will with human rational will as the legislator of moral laws. However, Kant himself explicitly stated that "morality inevitably leads to religion". This apparent contradiction implies a deeper purpose: Kant might have been attempting to provide a

rational and defensible foundation for religion in an era increasingly characterized by skepticism towards traditional revelation and dogma. By grounding religion in universal moral reason, he sought to make it immune to empirical disproof and speculative critique. This suggests that Kant was not fundamentally hostile to religion, but rather to its uncritical, dogmatic, and heteronomous forms. His reinterpretation can be seen as an effort to "save" a core concept of God and faith for modern thought, albeit in a highly reinterpreted form that emphasizes its ethical dimension and compatibility with human autonomy. His work thus sought to ensure the continued relevance of religious concepts in a world increasingly shaped by scientific and philosophical reason.

6. Scholarly Interpretations: The Ongoing Debate

The question of Immanuel Kant's religious views remains a subject of considerable and often passionate scholarly debate. There is no single, universally accepted classification for his stance on God, leading to diverse interpretations that highlight the inherent complexity and sophistication of his philosophical system.

Some scholars, such as Manfred Kuehn, have controversially alleged that Kant was an atheist, while others contend he was primarily an agnostic. His principled agnosticism regarding theoretical knowledge of God is widely acknowledged. He is very frequently characterized as a "moral believer" or as advocating a "moral faith". This interpretation emphasizes that his belief in God stems from the necessities of practical reason, rather than theoretical knowledge. Due to his rejection of divine intervention in the natural world and his emphasis on God as a "regulative" rather than "constitutive" principle, some scholars find deistic leanings in his philosophy. However, his moral argument for God's active role in ensuring the highest good distinguishes him from a purely distant, non-intervening deistic creator. Despite his philosophical critiques and his reported non-attendance at religious services, Kant was raised Pietist (a form of Lutheranism) and did purport to be a Christian. He defended the essential truth of some core Christian doctrines, such as original sin, though his interpretations were often considered highly heterodox by his contemporaries. Whether this makes him a "Christian" in a traditional sense is debated, with some arguing he fits within "liberal theology". The main divide in the scholarly literature often lies between "reductivist" or "deflationist" interpretations, which view Kant's conception of God as a "formal kind of subjectivity" or a "figment of the human imagination" with no true ontological status, and those who argue that Kant's philosophy offers a more ambitious claim about our entitlement to believe in God's actual existence.

Kant's philosophical system is built upon a rigorous separation between theoretical knowledge (what can be known through experience and understanding) and practical belief (what must be assumed for moral action). Yet, the available information reveals a palpable tension between this strict philosophical framework and Kant's personal background and apparent religious conviction. He was raised in the Pietist tradition, a devout form of Lutheranism, and he "purported to be a Christian," even defending certain Christian doctrines, albeit with heterodox interpretations. This leads to significant scholarly debate regarding how seriously one should interpret his personal religious claims versus the strict implications of his philosophical system. This suggests that Kant himself might have navigated a complex internal landscape, attempting to reconcile his deeply ingrained religious upbringing and personal faith with the radical, rational demands of his critical philosophy. The "head-scratcher" nature of his account of faith might stem from this very tension, where the philosophical justification for belief is distinct from, yet aims to support, a lived religious orientation, highlighting the human element within his abstract system.

A key point of contention is whether Kant's "God-talk" carries any "ontological oomph"—that is, whether it implies a real, independent existence for God beyond being a mere regulative idea or a necessary postulate of human reason. This debate underscores the inherent difficulty in reconciling Kant's critical limits with his affirmations of faith. Kant's "moral proof" for God's existence is rooted in practical commitment and the self-awareness of being a moral agent, rather than in theoretical cognition. This means it is a belief that is rationally required for moral consistency, not a truth claim about objective reality. He explicitly distinguishes between the mental state of holding "God exists" as theoretically true, which he denies is possible, and

taking "God exists" to be true in one's practical reasoning, which he affirms as necessary for moral faith. The concept of God in Kant's philosophy is often understood as analogical or symbolic, a way for reason to conceptualize the ultimate ground for the highest good, rather than a literal description of a divine being. Interpretations diverge on whether Kant genuinely believed in a divine providential order guiding humanity's destiny or if his use of "providence" refers to an immanent, impersonal dynamic of history.

While Kant is broadly considered a "theist of a unique kind" , his philosophical approach fundamentally redefines the nature of God and religious belief in ways that are often profoundly challenging for traditional, orthodox theism. By systematically discrediting traditional proofs for God's existence , by positing God as a postulate of practical reason rather than an object of theoretical knowledge , and by reducing religion to the recognition of moral duties as divine commands , Kant effectively "secularizes" or "moralizes" religion. This implies that for traditional believers, the "God" Kant speaks of might not be the transcendent, actively intervening, personal God of their faith. This highlights a significant ripple effect: Kant's philosophy, despite his stated intentions to "make room for faith," arguably paved the way for subsequent philosophical and theological movements that further distanced God from empirical reality and traditional religious practice. His work contributed to a more anthropocentric and immanent understanding of spirituality, where the divine is understood primarily through the lens of human reason and moral experience, rather than through external revelation or metaphysical proofs. His legacy is thus one of both profound critique and ambitious reconstruction, providing a framework for belief that resonates with modernity but often departs significantly from pre-critical religious understandings.

7. Conclusion: A Theist of a Unique Kind

In conclusion, the question of whether Immanuel Kant was a theist or an atheist cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." His philosophical system, characterized by its rigorous distinctions and profound insights, positions him uniquely beyond these conventional classifications. Kant was neither a traditional dogmatic theist who believed God's existence could be proven through speculative reason, nor an atheist who denied the possibility or necessity of belief in God.

Instead, Kant occupied a singular philosophical position best described as a moral theist. He was an

agnostic concerning the theoretical knowability of God , having systematically refuted all traditional metaphysical proofs for God's existence in his

Critique of Pure Reason. For Kant, God, as a transcendent being, is not an object accessible to human sensory experience or pure theoretical reason.

However, concurrently, he was a theist in the realm of practical reason. In his Critique of Practical Reason, Kant argued that belief in God is a necessary "postulate" for the coherence and rational pursuit of the moral life. This "moral faith" in God, alongside the postulates of freedom and the immortality of the soul, is considered essential for the possibility of achieving the "highest good" (Summum Bonum)—the state where virtue is perfectly aligned with proportionate happiness. God, in this context, serves as a moral legislator and the ultimate guarantor of justice, ensuring that moral striving is not ultimately futile. Kant's philosophy makes it clear that while his ethics are grounded in reason and do not

depend on God for their motivational force, the full rational coherence of the moral project requires the postulate of God. His concept of God functions as a regulative principle for reason and provides a framework for understanding all duties as if they were divine commands.

The central paradox of Kant's position lies in his assertion that belief in God is necessary for practical reason, despite his concurrent argument that theoretical knowledge of God is impossible. This poses a profound question: how can something be "necessary" for reason if its existence cannot be known or proven? Kant resolves this by defining "necessity" here not as logical or empirical certainty, but as a practical, moral imperative. Individuals

must believe in God to make coherent sense of their moral striving and to uphold the possibility of the highest good. This indicates that Kant is not offering a weak or provisional form of belief, but a robust, albeit non-theoretical, form of rational commitment. It represents a "belief-as-if" that, by virtue of its moral indispensability, transforms into a "belief-must-be," demonstrating the unique power and demands of practical reason in his philosophy.

By fundamentally shifting the ground of religious belief from external proofs and traditional revelation to the internal necessity of moral reason, Kant profoundly influenced subsequent philosophical and theological thought. His work laid crucial groundwork for the development of liberal theology, which emphasizes the ethical and experiential dimensions of faith over strict dogma, and even, indirectly, for secular humanism, by demonstrating how morality can be autonomously derived. This implies that Kant's impact extends far beyond academic philosophy, shaping how modern individuals and intellectual movements conceive of the relationship between ethics, reason, and religious faith. His legacy is one of both incisive critique and ambitious reconstruction, providing a framework for belief that seeks to be compatible with an increasingly rationalistic and autonomous modern world, albeit often at the cost of traditional theological interpretations.

In essence, Kant denied theoretical knowledge of God to make room for a practical faith, grounding religious belief in the moral demands of human reason itself. He was a theist, but one of a profoundly unique and influential kind, whose legacy continues to shape contemporary discussions on the relationship between reason, morality, and religion.

Table 1: Kant's Stance on God vs. Traditional Theism and Atheism

| Aspect of Belief | Traditional Theism | Atheism | Kant's "Moral Theism" |

| Source of God's Existence | Theoretical proofs (Ontological, Cosmological, Teleological), Divine Revelation | No belief in deities; rejection of proofs | Not theoretical knowledge; a "postulate" of practical reason |

| Nature of God | Knowable (to some extent); often intervening; personal | Non-existent | Unknowable theoretically; a "regulative" idea for reason; a moral legislator; guarantor of highest good |

| Relationship to Morality | God's commands are the source and foundation of morality | Morality is autonomous and independent of God's existence | Morality is autonomous (from reason itself); belief in God is necessary for the coherence and possibility of the "highest good" |

| Basis of Belief | Knowledge/Certainty derived from proofs or revelation | Lack of evidence/rejection of claims | "Moral Faith" / Practical Necessity; not theoretical cognition |