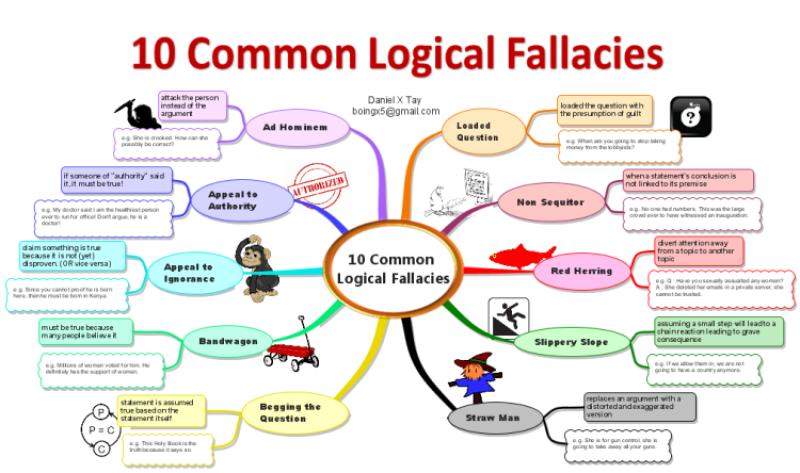

What are examples of rhetorical fallacies?

Rhetorical fallacies are errors in reasoning that can make an argument invalid or misleading. These fallacies often exploit emotional triggers or rely on faulty logic to persuade an audience. Here are some common examples of rhetorical fallacies:

Ad Hominem:

- Attacking the person making the argument rather than addressing the argument itself. For example, "You can't trust their economic policy because they're not even good with their personal finances."

Straw Man:

- Misrepresenting or exaggerating someone's argument to make it easier to attack. For example, "Opponents of the tax plan want everyone to be poor and unemployed."

Appeal to Emotion:

- Manipulating emotions to distract from the facts. For example, using a heart-wrenching story to argue against a policy without addressing its merits.

Appeal to Authority:

- Relying on the opinion of an authority figure rather than presenting a solid argument. For example, "Dr. Smith says this diet pill works, so it must be effective."

False Dichotomy (False Dilemma):

- Presenting only two options as if they are the only possibilities when, in reality, more exist. For example, "Either we ban all cars, or the environment will be destroyed."

Hasty Generalization:

- Drawing a conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. For example, "I met two people from that city, and they were both rude, so everyone from that city must be rude."

Circular Reasoning:

- Using the conclusion of the argument as one of its premises. For example, "The Bible is true because it says it is, and we can trust what it says."

Post Hoc (False Cause):

- Assuming that because one event follows another, the first event caused the second. For example, "I wore my lucky socks and aced the test, so the socks must be lucky."

Appeal to Ignorance:

- Arguing that a claim is true because it has not been proven false, or vice versa. For example, "No one can prove that aliens don't exist, so they must exist."

Red Herring:

- Introducing irrelevant information to divert attention from the real issue. For example, when asked about a controversial policy, a politician might bring up an unrelated issue to distract from the original question.

Appeal to Tradition:

- Arguing that something is right or good because it's always been done that way. For example, "This is how we've always done it; it must be the best way."

Bandwagon Appeal:

- Arguing that something is true or good because many people believe or do it. For example, "Everyone is using this new app; you should too!"

Recognizing these fallacies is important for critical thinking and evaluating the strength of arguments. It's crucial to be aware of logical errors to construct and assess arguments effectively.

Common Types of Rhetorical Fallacies and Their Impact on Arguments

Rhetorical fallacies are errors in reasoning that can weaken or invalidate an argument. They are often used to appeal to emotions or prejudices rather than logic and evidence. Here are some common types of rhetorical fallacies and their impact on arguments:

Ad hominem attacks: These attacks target the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. They can be used to discredit the speaker or distract from the issue at hand.

Appeal to emotion: This fallacy appeals to the audience's emotions, such as fear, pity, or anger, in order to persuade them rather than relying on logic and evidence.

Hasty generalization: This fallacy involves drawing a conclusion about a group of people or things based on a small or unrepresentative sample.

False analogy: This fallacy compares two things that are not really alike in order to make a point.

Slippery slope: This fallacy assumes that taking one step will inevitably lead to a series of increasingly negative consequences.

Straw man: This fallacy involves misrepresenting or oversimplifying an opponent's argument in order to make it easier to attack.

Begging the question: This fallacy assumes the truth of the conclusion that is supposed to be proven.

Recognizing and Avoiding Rhetorical Fallacies in Persuasive Writing

To recognize and avoid rhetorical fallacies in persuasive writing, it is important to be aware of the different types of fallacies and how they are used. Here are some tips:

Define your terms: Make sure that you and your audience agree on the meaning of the key terms in your argument.

Use clear and concise language: Avoid using jargon or overly technical language that your audience may not understand.

Provide evidence to support your claims: Don't rely on personal opinions or unsupported assertions.

Consider counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints.

Have someone else review your writing: A fresh pair of eyes can help you spot any fallacies that you may have missed.

Identifying Rhetorical Fallacies in Everyday Language and Discourse

Rhetorical fallacies are not just found in academic writing; they are also used in everyday language and discourse. Here are some examples of how rhetorical fallacies can be used in everyday conversation:

"You're just being mean." (Ad hominem attack)

"If we don't ban video games, our kids will all become violent criminals." (Slippery slope)

"My car is the best car on the market because it won the award for 'Most Likely to Impress Your Friends.'" (Appeal to emotion)

"All politicians are corrupt." (Hasty generalization)

"If you don't vote for me, you're voting for the devil." (False dichotomy)

Being able to identify rhetorical fallacies in everyday language can help you to be a more critical consumer of information. It can also help you to avoid using fallacies in your own communication.