What is the logical structure of argument?

Logical reasoning is the bedrock of clear thinking, effective debate, and persuasive communication. It's the silent scaffolding that supports every well-formed idea, allowing us to connect thoughts, build understanding, and arrive at justified conclusions. From the intricate arguments in academic essays and scientific papers to the everyday discussions we have with friends and family, the ability to reason logically is a fundamental human skill that underpins our capacity to make sense of the world.

At its core, every solid argument, regardless of its complexity, relies on a structured framework that coherently links ideas. Without this underlying logical structure, arguments can devolve into mere assertions, emotional appeals, or confusing statements that fail to convince or enlighten. Understanding this framework is not just for philosophers or debaters; it's a vital tool for anyone who wishes to think critically, communicate effectively, and avoid manipulation.

This article will guide you through the fundamental components of an argument's logical structure. We will explore the core elements that make up any argument—premises and conclusions—and illustrate how they work together to form coherent reasoning. We'll delve into common types of logical arguments, equip you with the skills to identify weak or flawed reasoning, and ultimately demonstrate how mastering the art of logic strengthens your critical thinking abilities in all aspects of life.

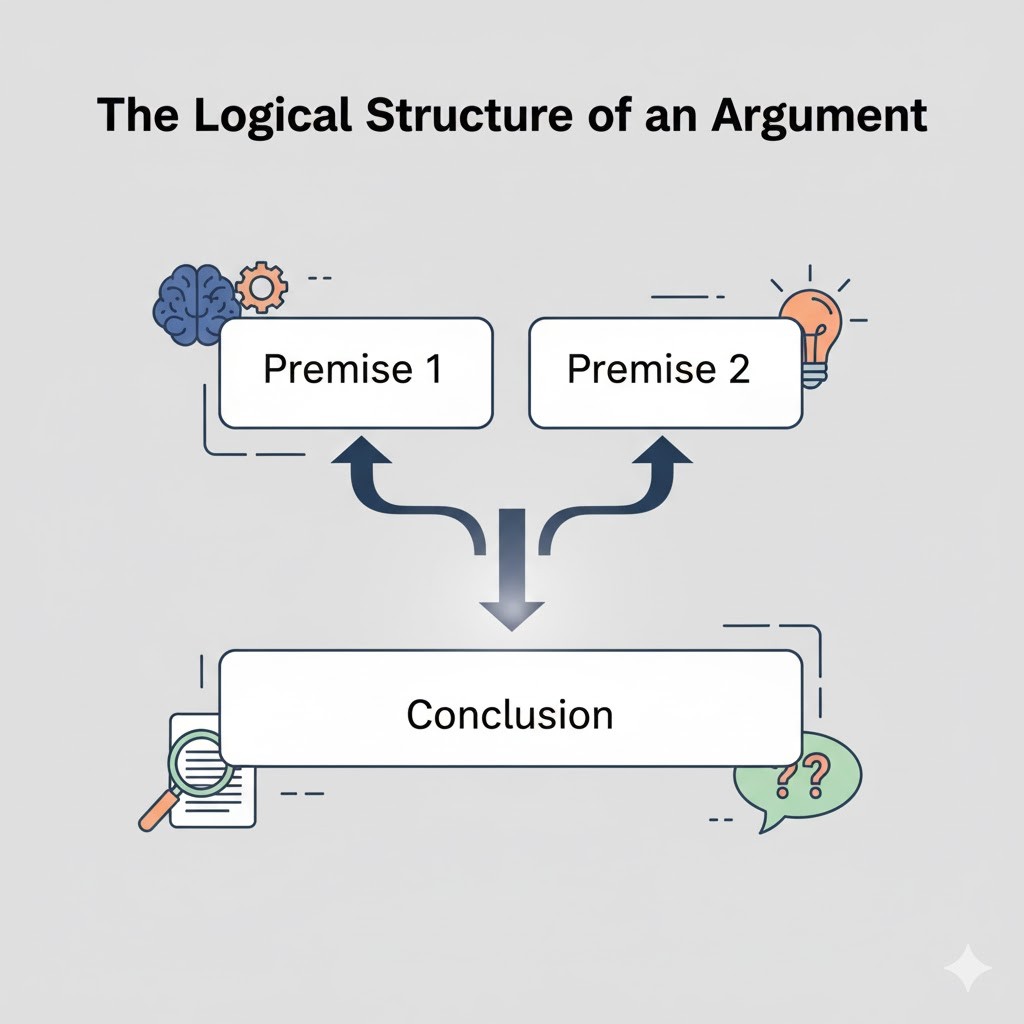

What Is the Logical Structure of an Argument?

The logical structure of an argument refers to the framework or arrangement that organizes reasoning to support a particular conclusion. It’s the skeleton upon which the body of an argument is built, ensuring that ideas are connected in a way that makes sense and provides justification. When an argument possesses a sound logical structure, its conclusion follows naturally and often necessarily from the evidence or reasons provided.

Every argument, regardless of its subject matter or complexity, consists of two fundamental parts:

Premises: These are the statements, reasons, or pieces of evidence that are offered to support or justify the conclusion. Premises are the assumptions you are asking your audience to accept as true, at least for the sake of the argument. Think of them as the building blocks.

Conclusion: This is the main claim, assertion, or point that the argument is trying to establish. It's what the arguer wants you to believe or accept, based on the premises provided. It's the completed structure.

Consider a classic, simple example to illustrate this:

Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

Premise 2: Socrates is a human.

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

In this example, the first two statements (Premise 1 and Premise 2) provide the reasons why we should accept the third statement (the Conclusion). The structure itself is clear: if you accept that all humans will die, and you accept that Socrates is a human being, then the death of Socrates logically follows.

The clarity and consistency of how these premises lead to the conclusion are what make reasoning valid and persuasive. A well-structured argument ensures that the path from evidence to claim is transparent, allowing others to follow your thought process and assess the strength of your reasoning. It's not just about what you say, but how you connect your statements to form a coherent and compelling whole.

How Do Premises and Conclusions Work Together in Reasoning?

Premises and conclusions are the gears and levers of reasoning, working in tandem to move an argument forward. The premises lay the groundwork, providing the factual assertions, definitions, or evidence that the arguer believes to be true. The conclusion then takes these accepted truths and, through a process of inference, derives a new statement that is intended to be supported by those truths.

There are two primary ways in which premises work to support a conclusion:

Deductive Reasoning: In deductive arguments, if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. The conclusion follows with certainty from the premises. Deductive reasoning moves from general principles to specific conclusions. It aims for validity, meaning that if the premises are true, the conclusion cannot be false.

Example (Deductive):

Premise 1: All mammals are warm-blooded. (General rule)

Premise 2: Dolphins are mammals. (Specific instance fitting the rule)

Conclusion: Therefore, dolphins are warm-blooded. (Certain specific conclusion)

In this deductive argument, if the first two premises are accepted as true, there is no logical way for the conclusion to be false. The conclusion is contained within the premises.

Inductive Reasoning: In inductive arguments, the premises provide strong support for the conclusion, but the conclusion is not absolutely guaranteed to be true, even if the premises are. The conclusion is probable, not certain. Inductive reasoning often moves from specific observations to broader generalizations.

Example (Inductive):

Premise 1: The sun has risen every day in recorded history. (Specific observations)

Conclusion: Therefore, the sun will rise tomorrow. (Probable generalization)

While the conclusion here is highly probable given the overwhelming evidence, it’s not impossible for it to be false (e.g., if the Earth stopped rotating or a catastrophic cosmic event occurred). Inductive arguments aim for strength, meaning that if the premises are true, the conclusion is very likely to be true.

The effectiveness of an argument hinges on how well the premises logically connect to the claim, without any missing steps, unexplained jumps, or internal contradictions. A strong argument ensures that there are no gaps in the reasoning, making it difficult for an audience to accept the premises but reject the conclusion. The synergy between premises and conclusions is what allows ideas to be built upon and understood systematically.

What Are Common Types of Logical Arguments?

Understanding the various types of logical arguments is crucial for both constructing robust arguments and deconstructing those presented by others. Each type has a distinct structure and is suited for different kinds of reasoning.

Deductive Arguments:

Description: These arguments start with one or more general statements or rules and then apply them to a specific case to reach a specific, certain conclusion. If the general premises are true, the specific conclusion must be true.

Example:

Premise 1: All equilateral triangles have three equal sides.

Premise 2: Triangle ABC is an equilateral triangle.

Conclusion: Therefore, Triangle ABC has three equal sides.

Goal: To prove a conclusion with certainty.

Inductive Arguments:

Description: These arguments draw general conclusions from specific observations or examples. They aim to establish a high probability for the conclusion, not certainty. The conclusion goes beyond the information explicitly stated in the premises.

Example:

Premise 1: Every raven I have ever seen is black.

Premise 2: All other people I've asked have also only seen black ravens.

Conclusion: Therefore, all ravens are black.

Goal: To establish a probable generalization or prediction.

Abductive Reasoning:

Description: This type of reasoning starts with an observation or a set of observations and then seeks the simplest and most likely explanation for those observations. It involves making an inference to the best explanation. The conclusion is a hypothesis that makes the premises most plausible.

Example:

Premise 1: The grass on the lawn is wet.

Premise 2: The sprinkler was not on.

Conclusion: Therefore, it probably rained.

Goal: To formulate the most plausible hypothesis given limited evidence.

Analogical Reasoning:

Description: This involves drawing a conclusion about one thing (the target) based on its similarities to another thing (the source) that is better understood. If two things are similar in several known respects, they are likely to be similar in another unknown respect.

Example:

Premise 1: Learning to play a musical instrument requires patience, practice, and dedication.

Premise 2: Learning to code is similar to learning a musical instrument, as both involve mastering complex patterns and systems.

Conclusion: Therefore, learning to code also requires patience, practice, and dedication.

Goal: To illuminate or predict based on comparison.

These various forms highlight how different logical strategies are employed to construct arguments. Recognizing which type of argument is being used helps in critically evaluating its claims and the strength of its support.

How Can You Identify Weak or Flawed Arguments?

Even with the correct logical structure of an argument, an argument can still be weak or flawed if its premises are false, or if the reasoning connecting premises to conclusion is faulty. The ability to identify flawed arguments is a cornerstone of critical thinking, protecting you from manipulation and helping you make informed decisions. Errors in reasoning are known as logical fallacies.

Here are examples of common logical fallacies:

Strawman: This fallacy occurs when someone misrepresents or distorts an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack. Instead of engaging with the actual argument, they create a "straw man" version that is easily defeated.

Example:

Person A: "I think we should invest more in renewable energy."

Person B: "So you're saying we should completely shut down all fossil fuel industries tomorrow and plunge the economy into chaos? That's unrealistic." (Person B misrepresented Person A's argument.)

Ad Hominem (To the person): This fallacy involves attacking the character, motives, or other attributes of the person making the argument, rather than addressing the substance of the argument itself.

Example: "You can't trust Dr. Smith's research on climate change; he's just a disgruntled scientist who lost funding." (Attacks Dr. Smith, not the research findings.)

False Cause (Post hoc ergo propter hoc - after this, therefore because of this): This fallacy assumes that because one event happened after another, the first event must have caused the second. It confuses correlation with causation.

Example: "Sales increased right after we changed our logo. Clearly, the new logo is responsible for our improved revenue." (Could be other factors at play, like market conditions or a new product.)

Slippery Slope: This fallacy claims that a relatively minor first step will inevitably lead to a chain of related, usually negative, and often extreme consequences.

Example: "If we allow students to use calculators in basic math classes, they'll never learn mental arithmetic, then they'll fail algebra, and soon our entire education system will collapse!"

To effectively evaluate reasoning and spot these flaws, you can employ a simple 3-step test:

Are the premises true or adequately supported by credible evidence? This is the first and most crucial step. If the foundational statements are false or lack support, the entire argument crumbles, regardless of its structure.

Do the premises logically lead to the conclusion? Even if premises are true, they must connect rationally to the conclusion. Look for gaps in reasoning, unjustified leaps, or conclusions that don't actually follow from the evidence provided. This is where fallacies like false cause or slippery slope often occur.

Are there hidden assumptions or emotional appeals replacing logic? Strong arguments rely on evidence and reason, not on manipulating emotions or relying on unstated beliefs. Be wary of arguments that play on fear, pity, or personal biases, or that make assumptions that are not explicitly stated and justified.

By systematically applying this test, you can sharpen your ability to critically assess arguments, distinguish sound reasoning from mere rhetoric, and avoid being swayed by flawed logic.

How Does Understanding Logical Structure Improve Critical Thinking?

The study and application of the logical structure of an argument are paramount to developing robust critical thinking and logic skills. It's not merely an academic exercise; it fundamentally enhances how we process information, form beliefs, and interact with the world around us.

Here’s how understanding logical structure improves critical thinking:

Enhances Clarity and Precision in Reasoning: When you understand premises and conclusions, you learn to articulate your thoughts with greater precision. You become adept at breaking down complex ideas into their foundational components, ensuring that each step of your reasoning is clear, explicit, and well-supported. This clarity minimizes ambiguity and strengthens your ability to communicate your ideas effectively.

Improves Fairness and Objectivity in Evaluation: By focusing on the structure of an argument rather than the person presenting it or your emotional reaction to the topic, you can evaluate ideas more objectively. You learn to separate the validity of the reasoning from your personal biases or the argument's emotional appeal, leading to fairer assessments.

Strengthens Academic Writing and Argumentation: In academic contexts, logical structure is non-negotiable. Understanding how to build a coherent argument with clear premises and a justified conclusion is essential for writing persuasive essays, conducting rigorous research, and defending your findings. It allows you to construct compelling arguments that withstand scrutiny.

Boosts Debating and Public Speaking Skills: When engaging in debates or delivering speeches, a solid grasp of logic enables you to anticipate counter-arguments, identify weaknesses in opponents' reasoning, and present your own case with compelling evidence and logical progression. This leads to more impactful and convincing communication.

Informs Decision-Making in Business and Everyday Life: From strategic business decisions to personal choices, logical thinking is invaluable. Analyzing options by identifying their underlying premises, evaluating potential outcomes, and spotting potential fallacies in proposed solutions helps you make more rational, evidence-based decisions, reducing the risk of errors or unintended consequences.

Protects Against Manipulation and Bias: In an age of information overload and pervasive persuasion (from advertising to political rhetoric), the ability to dissect an argument's logical structure is a powerful defense mechanism. For example, by analyzing a news article or a political speech through the lens of logic, you can quickly identify unsupported claims, misleading statistics, or emotional appeals replacing sound reasoning. This helps you avoid manipulation and form your own informed opinions.

Example: When reading a news article, instead of just accepting its headline, ask yourself: What are the premises being presented? Is there data or expert opinion backing them? What is the explicit or implicit conclusion? Does the conclusion logically follow, or are there gaps? Are there any logical fallacies at play?

Encouraging readers to apply logical analysis to evaluate everyday claims—whether from social media posts, advertisements, or political debates—is key. This active engagement with logical principles transforms passive consumption of information into active, critical engagement, fostering intellectual independence and resilience.

Table Idea: Types of Logical Reasoning

| Type | Description | Example |

| Deductive | From general rule to specific case (certainty) | All birds have feathers → A robin is a bird → A robin has feathers. |

| Inductive | From specific cases to general rule (probability) | Every swan seen so far is white → All swans are white. |

| Abductive | Best explanation from limited facts (hypothesis) | The neighbor's dog is barking unusually loudly → Someone is at the door. |

| Analogical | Comparison-based reasoning (similarity inference) | Learning to code is like learning a new language; both require immersion. |

FAQ Section:

What is the difference between logic and argumentation?

Logic is the study of correct reasoning, principles of valid inference, and the formal structures of thought. It's the theoretical framework and the rules.Argumentation is the practical act of constructing and presenting arguments to persuade, inform, or justify. It involves applying logical principles, but also considers rhetoric, context, audience, and evidence. Logic provides the blueprints, argumentation builds the house.

Can an argument be logical but still false?

Yes, absolutely. An argument can be logically valid (meaning its conclusion necessarily follows from its premises) but still have a false conclusion if one or more of its premises are false. Such an argument is considered unsound.

Example:

Premise 1: All cats can fly. (False premise)

Premise 2: My pet is a cat. (True premise)

Conclusion: Therefore, my pet can fly. (Logically valid, but unsound because Premise 1 is false).

What are examples of valid but unsound arguments?

Building on the previous answer, an argument is valid if its structure guarantees that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. It's unsound if it's valid, but at least one premise is actually false.

Example 1:

Premise 1: All fish can walk. (False)

Premise 2: A shark is a fish. (True)

Conclusion: Therefore, a shark can walk. (Valid structure, false conclusion due to false premise).

Example 2:

Premise 1: If it rains, the streets get wet. (True)

Premise 2: It is raining. (False, let's assume it's sunny)

Conclusion: Therefore, the streets are wet. (Valid structure, false conclusion due to false premise).

How can I improve my logical reasoning skills?

Practice identifying premises and conclusions: Take any piece of text (news article, essay, speech) and try to break it down into its core arguments.

Study logical fallacies: Familiarize yourself with common errors in reasoning so you can spot them in your own thinking and others'.

Engage in debates and discussions: Actively participate, but focus on the structure of arguments rather than just winning.

Read philosophical and critical thinking texts: Many resources offer exercises and deeper dives into logical principles.

Solve logic puzzles: Games and puzzles designed for logic can sharpen your analytical mind.

Question assumptions: Always ask "Why?" and "What evidence supports that?" to dig deeper than surface-level claims.

Conclusion

The logical structure of an argument is the invisible yet essential framework that transforms scattered ideas into clear, persuasive reasoning. By understanding that every sound argument is built upon a foundation of premises supporting a conclusion, you gain a powerful tool for navigating the complexities of information and communication. Whether through the certainty of deductive reasoning or the probability of inductive inference, the coherent connection between evidence and claim is what gives an argument its strength.

Mastering this understanding not only enables you to craft stronger, more convincing arguments of your own but also equips you with the critical faculties to identify flawed arguments and resist manipulation. By recognizing common logical fallacies and applying a systematic approach to evaluating claims, you enhance your critical thinking and logic skills, fostering precision, objectivity, and intellectual independence.

We encourage you to practice analyzing everyday claims—from social media posts and advertisements to political debates and news reports—through the lens of logic and evidence. This active engagement will sharpen your mind, allowing you to discern sound reasoning from rhetoric, make wiser decisions, and contribute more thoughtfully to every discussion. The ability to think logically is not just an academic pursuit; it is a fundamental skill for thriving in an increasingly complex world.

PhilosophyFan

on October 11, 2025The FAQ addressed a great point: an argument can be logically valid but still false (unsound). That distinction is often missed by beginners.

AnalogicalAbe

on October 11, 2025The table comparing the four types of logical reasoning is fantastic for quick reference. Analogy-based arguments are often tricky, but the explanation helps.